On

Wednesday evening, February 17, 2016, ‘Writers of Central Florida or Thereabouts’, allowed me the opportunity to read a passage from my book, ‘First Road to Orlando.’ If I can help it, I never pass up an opportunity to discuss the fascinating story of 19th

Century Central Florida, especially of how an old forts trail, twinning its way

south from Lake Monroe in 1836, from

Fort Mellon in the north to Fort Gatlin in the south, evolved

into the Mellonville Road, a/k/a, First Road to Orlando

Along a 28 mile old forts trail, settlers

in 1842 began building towns of Mellonville, Fort Reid, and Fort Gatlin.

Towns of Rutledge, Maitland and Orlando came on the scene thereafter, with all but Rutledge

pre-dating the first train to run south from Lake Monroe, which departed

Sanford, November 11, 1880.

I

selected for my reading Chapter 11, Who

to Believe? I chose this chapter because to me, it provides as well a

window into the intriguing mystery

that surrounds nearly all of Central Florida early history. How Orlando got its name, for example, has long been a topic of debate.

FIRST ROAD TO ORLANDO:

CHAPTER 11: WHO TO

BELIEVE?

Samuel S. Griffin, in 1923

a resident of Orlando for more than 40

years, spoke to the Orlando’s Sorosis Club on the subject of their

town’s history, and of how Orlando had been named. Griffin used 14 pages of typed notes for his speech,

a document now safely stored in Central Florida archives.

He

told the members that Mr. Fries had told

him, “the story of the Indian killing on

the banks of one of their beautiful lakes.” A soldier standing guard while

others slept, Sam had said, was attacked and killed by Indians.

John O. Fries, a Swedish immigrant who became County

Surveyor, arrived in Orlando on Christmas Day, 1871. The City of Orlando was at that time 14 years old.

Orange County Surveyor, John Otto Fries

Griffin

then told the membership that S. A.

Robinson had given him a different version, stating Robinson claimed his

version came from Arthur Speer, the

son of Judge James G. Speer. “A man named Orlando became very ill here and was taken into Judge Speer’s home,

and cared for.” Having become friends, as this particular naming of Orlando

goes, Judge James Speer named the town for that fellow.

Samuel A. Robinson was also a County Surveyor, and drew the

first sketch of what 1857 Village of

Orlando looked like. He drew that town plat in 1880.

Orange County Surveyor, Samuel A. Robinson

Samuel

S. Griffin then said he was told a third version by B. M. Robinson, stating that Robinson, “Most emphatically declared Judge Speer was a great lover of Shakespeare”,

so Speer named the town for a character in the play, “AS YOU LIKE IT.” Benjamin M. Robinson had been a

three-term Orlando Mayor. He arrived in Central Florida around 1872.

Three Term Orlando Mayor, Benjamin M. Robinson

Concluding

his story of the three versions as to how the town of Orlando got its name,

Samuel S. Griffin declared, “I dared

not ask another how Orlando got its name!”

The

many versions as to how Orlando had been named have progressed over the years:

1915: Clarence

E. Howard published his book, ‘Early Settlers of Orange County Florida,” in

which was included a biography on Judge J. G. Speer, stating: “At once the question of a name came up and

was named ‘Orlando’ by Judge Speer for one of Shakespeare’s characters.”

Orlando Photographer, Clarence E. Howard

1923: Samuel S. Griffin addressed the Orlando

Sorosis Club and reported on three versions told to him.

1927: William

Fremont Blackman, Rollins College President, wrote his, ‘History of Orange

County, Florida,’ in which he also tells of three versions, similar to

Griffin’s, although adding a few details. Blackman said: (1) Orlando Reeves was the soldier’s name,

and the ambush took place at ‘Hughey

Bay’; (2) The ‘sick’ fellow taken in by Judge Speer was actually an

employee of Speer’s who, after his death, the village was named for; and (3)

Speer was said to be a lover of, and student of, William Shakespeare.

Rollins College President, William Fremont Blackman

1938: Kena

Fries published her book, ‘Orlando in the Long, Long Ago’, in which she

stated, “Many versions have been given

and many tales told.” Kena, daughter of John O. Fries, was convinced the

legend of Orlando Reeves was the legitimate

version. She said her father had been told this story by ‘gray haired, widely scattered pioneers.” Kena’s version included

details of the incident never before told.

Kena

Fries reported that the incident occurred on a full moon night in September, 1835. Fellow soldiers had fallen off

asleep while Orlando Reeves kept a ‘vigilant watch’. After several hours,

himself fighting off sleep, Orlando

Reeves noticed what he thought at first to be a log, floating in Lake Eola. “Realizing they were Indians stealthily creeping on the camp, he gave

the alarm, knowing full well it meant death to him and he fell, pierced by more

than a dozen poisoned arrows.”

The

body of Orlando Reeves, Kena said,

was buried in a grave beside Lake Lawson,

“beneath a tall pine tree, a landmark on the

trail.”

1951: E.

H. Gore wrote his, ‘From Florida Sand to the City Beautiful, A Historical

Record of Orlando, Florida’, in which he too offers various versions of how the

town was named.

Gore

said some early settlers believed John

R. Worthington, the city’s first Postmaster, named their town, while others

believed Judge James G. Speer, “a student of Shakespeare,” named the city

“for one of the characters in

Shakespeare’s, AS YOU LIKE IT.”

Gore

then wrote: “the story that finally won out and was adopted as authentic in

regard to the name was told by early settlers about Orlando Reeves.” Gore’s reference in saying won out suggests

this version was selected through a popularity contest.

Gore’s

version also changes the location, stating the Indian attack occurred “on the east side of Lake Minnie (Now

Cherokee).” The body of Orlando in Gore’s version was said to be buried

under an oak tree at Lake Eola, but he also stated that another version says

Orlando Reeves was buried under a pine tree at Lake Lawson, and that that tree has since been cut down.

Gore

stated a pioneer who had lived in Orlando since 1883 told him the Orlando Reeves’ grave was under the oak tree at Lake Eola when that pioneer first

arrived. Settlers and soldiers, Gore was told, visited this grave and had

handed down the story.

There

is another version never told by local historians, but most certainly

worthy of inclusion here. Volusia County has long suggested Orlando was named

for a plantation owner, ORLANDO SAVAGE

REES.

Similarities

in the names REES and REEVES, and the two stories, is

interesting.

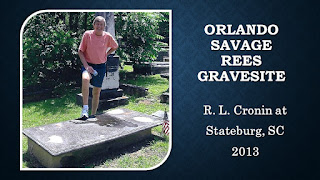

Richard Cronin at South Carolina grave site of Orlando Savage Rees

Kena

Fries began her Chapter 2, ORLANDO - THE NAME, by stating “many versions have been given and many tales told. All are true, more

or less, yet no two agree.” If no two agree, as they do not, then in my

mind, it is not reasonable to suggest all are true.

What

is the truth? Who should we believe? We will examine each and every known version as to how Orlando got its name, and do so having an advantage over earlier

historical attempts. We now have access to the vast World Wide Web, data

earlier historians did not have at their fingertips. Our goal is to solve a timeless

mystery, who named Orlando?

First

road to Orlando includes a 21 page Bibliography