FORT MELLON MONTH, Part 4 of 4

Doyle and Brantley at Mellonville

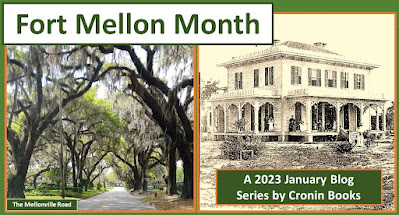

Mellonville

Road of today and yesteryear’s Doyle Residence at Mellonville

More like that of a scene out of a Wild-West picture show, it’s not easy today to imagine 300 to 400 painted warriors storming the Lake Monroe beach in their attack on Encampment Monroe. A fierce battle however did in fact occur on the south shore of Lake Monroe on 8 February 1837, a Seminole Indian War clash which forever changed Central Florida.

The

Grave of Capt. Charles Mellon

The most noticeable change occurred within days of the

incident, with Encampment Monroe being renamed Fort Mellon in honor of the one

fallen comrade, Captain Charles Mellon (Part III). The battle of 8 February

1837 was but the beginning of a series of claimed land ownerships that, by the 1880s,

would officially establish a gateway for Central Florida settlers.

Coming

in February: Fort Gatlin Month

While the Army fought for control of Lake Monroe’s

south shore in 1837, a battle of a different nature was already underway at the

U. S. Supreme Court in Washington, DC. A Morocco native named Moses was arguing

before the court that the very same Florida Territory property, 12,000 acres to

be exact, rightfully belonged to him. Spain, said Moses E. Levy, had granted this

land to him, and on these 12,000 acres he planned to establish a homeland for

persecuted Jews of Europe. Levy had won his case, but the United States filed

an appeal.

Spanish Land Grant map of 12,000 acres on Lake Valdez

Moses Elias Levy Grant

Lake

Valdez was renamed Lake Monroe

Meanwhile, back in the Florida Territory, two soldiers

of the Second Indian War, recruits from the North who survived the six-year War,

remained behind as their comrades began to pack up and return home. And the two

who stayed in 1842 forever changed Central Florida.

Henry A. Crane of New Jersey and Augustus J. Vaughn of

Virginia both remained at their posts – literally – after victory had been

declared. Crane and Vaughn became the first settlers, two of the bravest of brave

who claimed homesteads south of Lake Monroe.

Henry Crane homesteaded fortress Mellon and 160 acres

surrounding the abandoned fort. He established a settlement there, naming it

Mellonville. The pier on Fort Mellon built by the Army became a port of entry

for private citizens, a landing spot for the earliest steamboats to offload settlers

– more of the bravest of brave Central Florida pioneers.

Augustus Jefferson Vaughn homesteaded Fort Reid, a supply

fort 1.5 miles inland that had been established just prior to the end of the

War. Vaughn selected 160 acres which included the old fortress, and he too

established a settlement, naming it Fort Reid (misspelled Reed in 1846 by an early

surveyor). [A visitor to Fort Reid in 1873 met an “old gentleman,” Augustus

Vaughn, and asked if he could see the fort and its soldiers. Augustus Vaughn

replied, “This is the fort, and I am the soldier”]

Fort Mellon and Fort Reid were connected by a trail 1.5

miles long, the first part of a trail that was 22 miles long and known in the

1840s as the Fort Mellon to Fort Gatlin Road. In the 1850s this trail

became the Mellonville to Orlando Road, and, for the short portion still

in existence, is now known as Mellonville Road.

Coming

in March: SARASOTA Month

Settlements Mellonville and Fort Reid were both established

in 1842, prior to the Homestead Act Amendment requiring homesteaders to select

acreage at least two miles or more from an Army post. Central Florida pioneer

Aaron Jernigan arrived in 1843, desiring to homestead Fort Gatlin, but was

required instead to choose land that was two miles from the fortress Gatlin – a

story best told next week – during Fort Gatlin Month – our countdown to Pine

Castle Pioneer Days series.

As Mellonville began developing on the shore of Lake

Monroe at the old fortress, the Supreme court in Washington, DC, ever so slowly

deliberated the fate of the Moses Levy Grant. In 1850, 18 years after Levy had filed

his Spanish Land Grant lawsuit, a final decision was handed down giving Moses

E. Levy his land. Then a resident of St. Augustine, Levy was awarded all 12,000

acres, and the Court also ordered a surveyor to return to Central Florida to

establish boundaries of the Levy Grant.

Eastern

boundary of 1850 Mellonville Survey

Surveyor Arthur Randolph found half of Mellonville,

including the Lake Monroe wharf, to be located on property belonging to Moses

Elias Levy as of 1850. The 1842 Homestead of Henry A. Crane was voided, and Crane

thereafter departed Orange County.

Moses E. Levy sold his 12,000 acres on the south shore

of Lake Monroe to an Irishman, Joseph Finegan, who soon after became Florida’s

Brigadier General during the Civil War. Finegan sold his 12,000 mostly undeveloped

acres to a Northerner, Henry S. Sanford, who in turn sold most of his unsold

city of Sanford to a consortium of English Investors.

Although Joseph Finegan still owned most of the 12,000 acres in 1867, one small parcel had been sold to Michael J. Doyle and George C. Brantley, two Civil War veterans who decided to establish a General Store on the south shore of Lake Monroe near the old Fort Mellon Wharf. The Doyle & Brantley store welcomed a new generation of settlers to Orange County - a remarkable generation of dreamers - and doers - from around the globe.

In later years the gateway would shift one mile to the west, but during the 1870s, the First Road to Orlando opened the way to development of the Central Florida we know and love today.

My Five-Star Rated First Road to Orlando is available at Amazon.com

Available also at my CroninBooks Booth next to the HISTORY TENT

Pine Castle Pioneer Days, February 25 and 26, 2023

FORT GATLIN MONTH BEGINS

Next Wednesday, February 1, 2023

.jpg)

.jpg)